Faroes : Nolsoy

Introduction

Situated roughly half way between Scotland and Iceland in the Northeast Atlantic, the Faroe Islands are an archipelago of 18 mountainous islands, of which only one is uninhabited, with a total land area of some 1400 sq. km, a sea area of 274,000 sq. km and a population of approximately 49,000. The language of the Faroe Islands, Faroese, is a west Nordic language, which derives from the language of the Norsemen who settled the islands 1200 years ago. The country also has its own flag.

As a self-governing territory under the sovereignty of the Kingdom of Denmark, the Faroe Islands legislate and govern a wide range of areas in accordance with the Home Rule Act of 1948. These include the conservation and management of living marine resources within the 200-mile fisheries zone, sub-surface resources, trade, fiscal, industrial and environmental policies, transport, communications, culture, education and research. The Prime Minister’s Office maintains the formal contact between the Government and the Logting (Parliament), which today comprises 33 elected members and is one of the oldest in Europe.

As a self-governing territory under the sovereignty of the Kingdom of Denmark, the Faroe Islands legislate and govern a wide range of areas in accordance with the Home Rule Act of 1948. These include the conservation and management of living marine resources within the 200-mile fisheries zone, sub-surface resources, trade, fiscal, industrial and environmental policies, transport, communications, culture, education and research. The Prime Minister’s Office maintains the formal contact between the Government and the Logting (Parliament), which today comprises 33 elected members and is one of the oldest in Europe.

Though Denmark is a member of the European Union (EU), the Faroe Islands and Greenland, which is the third country in the Danish Kingdom, are not members of the EU. The Faroes negotiate their own trade and fisheries agreements with the EU and other countries, in consultation and cooperation with the Danish foreign ministry, and participate either independently or together with Greenland in a range of regional fisheries management bodies.

With an economy overwhelmingly dependent on the fishing and aquaculture industries, the Faroes are keenly aware of the need to strengthen Faroese capacity to deal with the challenges of a globalised world. Enhancing economic independence is a key factor in ensuring sustainable development and stimulating economic diversity.

For the purposes of this case study we are concentrating on the island of Nolsoy (that is approximately 5 km east of the capital Torshavn) and the eight Faroese outer islands which have their own Association (Utoyggjafelagid). Nolsoy is different compared to the other small islands where the population decreases and the average population age continuously increases. Nolsoy has, because of its proximity to Torshavn, managed to attract young people including several musicians who have settled on the island and started their own recording studio. There are few jobs and services on the outer islands where most people rely on sheep farming and tourism. Energy for heating is expensive on the outer islands and empty oil drums constitute an environmental problem that needs to be solved. Nevertheless, all these island communities have a very positive attitude towards greening their local economies.

For the purposes of this case study we are concentrating on the island of Nolsoy (that is approximately 5 km east of the capital Torshavn) and the eight Faroese outer islands which have their own Association (Utoyggjafelagid). Nolsoy is different compared to the other small islands where the population decreases and the average population age continuously increases. Nolsoy has, because of its proximity to Torshavn, managed to attract young people including several musicians who have settled on the island and started their own recording studio. There are few jobs and services on the outer islands where most people rely on sheep farming and tourism. Energy for heating is expensive on the outer islands and empty oil drums constitute an environmental problem that needs to be solved. Nevertheless, all these island communities have a very positive attitude towards greening their local economies.

Renewable Energy & Eco Housing

NOLSOY

In 2003 the Nordic Council of Ministers granted funding for the first of several feasibility studies on renewable energy systems and hydrogen energy technology for remote communities in the West Nordic region. The 10 sq. km island of Nolsoy was selected due to its potential for high wind energy and proximity to Torshavn. Also, it has a reasonable size of 100 households and 270 people with a representative population mix. There used to be a fishery at the island, but this was shut down in 2003. However, a new ferry has been planned for the island with an electrical propulsion system that can be fed by diesel or possibly hydrogen powered generators (or a combination of both). Because of the good traveling connection to Tórshavn, Nólsoy is a vital community where new houses are built and it has its own child care centre and school. The electrical power system at Nólsoy is operated by the power company SEV and consists of a 10kV sea cable with a capacity of 2 MW (connected to the main grid), a transforming station for the local mini-grid (400 V), and two back-up diesel generators (256 kW each). The heat demand is supplied by heating oil.

After various measurement, monitoring and other evaluation studies, the feasibility project for Nolsoy concluded that it made sense to design a wind/diesel system with thermal storage, both from a techno-economical and environmental point of view. Such systems can have close to 100% local utilization of the wind energy, and can cover up to 75% of the total annual electricity demand and 35% of the annual heat demand at a cost of energy around 0.07 – 0.09 euro/kWh. The cost of a hydrogen system was technically feasible, but doubles the overall investment costs. Once this feasibility study ended in 2007 the Faroese Earth & Energy Directorate (Jardfeingi) initiated further work with other partners to create a sustainable and independent energy supply for Nolsoy based on renewable sources and published a report. They focused on two technical solutions that have shown superior performance with respect to self sufficiency and economics.

The local power company SEV has faced the challenge of renewable energy head on combining hydropower and wind power to make 40% of the Faroese energy supply sustainable. Normal electricity production is spread out between 13 power plants, which produce according to demand. Three of these plants are thermal and six are hydroelectric. In addition to these there are five smaller plants providing power. SEV also has four windmills in Neshaga on Eysturoy and has initiated SeWave to develop a demonstration wave energy plant at Nipan on Vagar. The Faroese Earth & Energy Directorate (Jardfeingi) has been involved with Nolsoy – see box section – and with other projects like finding out if there is basis for using ground heat for warming of residential buildings instead of oil. They set up ground heat installations in 5 different houses situated at various places around the islands and early results are encouraging. There has also been a steady growth in the number of residential buildings using air to water heat pumps and small wind turbines. Further information on sustainable energy in the Faroe Islands can be obtained from this 2005 report.

The commercial scale wave energy scheme named Project Alda has obtained EU grant as well as local support and is planned to be in operation from 2011. The project so far developed and proposed is a tunneled wave energy converter (TWEC) system, based on Oscillating Water Column technology. SEV has also recently formed the GRANI partnership with Danish energy giant DONG to identify and test ways to reduce fossil-fuel dependence. This will include electrical heating, heat pumps, and perhaps most interestingly the use of electric cars. GRANI will also involve optimising output from renewable energy sources through new software concepts as well as significant expansion of the number of windmills.

Looking more into the future, the managing director of Faroese marine biotechnology company, Ocean Rainforest, together with another energy expert within Bitland Enterprise are developing a method of farming seaweed on the open ocean and thus attempting to realize the economic benefits of turning seaweed into various biofuels. This pioneering work also forms part of international projects like BlueGreenFuture and Future Climate that are working on cleantech solutions designed to address remediation of harmful emissions.

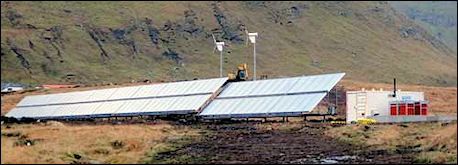

The Nordic Network for Sustainable Energy Systems in Isolated Locations has been very active. In October 2009 they organised a workshop on “Getting sustainable energy projects happening in small communities – practical issues” in Fuglafjordur, Faroe Islands, in collaboration with the newly established Faroe Islands Renewable Energy Centre in Kambsdalur and the Agenda 21 office. This event had various interesting presentations and workshops including one on ‘Greening Faroese Outer Islands’ that outlined their various renewable energy projects The first technologies to be demonstrated at the Kambsdalur Renewable Energy Centre itself are a large scale solar collector system, undergound heat pumps and a hydrogen system that makes it possible to store renewable energy and use it for transport. The Agenda 21 Group is working together with municipalities to make municipal buildings more energy efficient and to educate employees on energy saving measures.

The Nordic Network for Sustainable Energy Systems in Isolated Locations has been very active. In October 2009 they organised a workshop on “Getting sustainable energy projects happening in small communities – practical issues” in Fuglafjordur, Faroe Islands, in collaboration with the newly established Faroe Islands Renewable Energy Centre in Kambsdalur and the Agenda 21 office. This event had various interesting presentations and workshops including one on ‘Greening Faroese Outer Islands’ that outlined their various renewable energy projects The first technologies to be demonstrated at the Kambsdalur Renewable Energy Centre itself are a large scale solar collector system, undergound heat pumps and a hydrogen system that makes it possible to store renewable energy and use it for transport. The Agenda 21 Group is working together with municipalities to make municipal buildings more energy efficient and to educate employees on energy saving measures.

In December 2009 a design contract was won for the largest educational building project in the Faroe Islands' history. The new 19200 m² Education Centre in Marknagil, situated on a hillside on the outskirts of Torshavn, will serve as a base for coordination and future development of all educational programmes in the region. The new centre combines Faroe Islands Gymnasium, Torshavn’s Technical College and Business College of Faroe Islands in one building, housing 1200 students and 300 teachers.

The brainchild of Danish Architect Kari Thomsen and Engineer Ole Vanggaard, Easy Domes are a contemporary prefab home design with two ambitions – easy assembly and low energy. One short day can yield this totally functional and ultimately unique house. There are various designs ranging from the ‘Tuft 250’ to the Greenland Society cultural house in Torshavn. Composed of a single dome or a series, Easy Domes are all founded on the “icosahedron” shape, a collection hexagonal panels arranged to offer a layout maximizing interior living space. This futuristic design does not compromise the comforts of home, offering a two-storey layout complete with a living room, kitchen, bathroom and two bedrooms. Another modern twist on the traditional is that these homes are built using eco-friendly materials and methods. The design is vented on the exterior, and insulated with wood and flax. A green roof tops off these homes, complemented by solar roof panels, a wind turbine and other methods to harvest alternative forms of energy.

The brainchild of Danish Architect Kari Thomsen and Engineer Ole Vanggaard, Easy Domes are a contemporary prefab home design with two ambitions – easy assembly and low energy. One short day can yield this totally functional and ultimately unique house. There are various designs ranging from the ‘Tuft 250’ to the Greenland Society cultural house in Torshavn. Composed of a single dome or a series, Easy Domes are all founded on the “icosahedron” shape, a collection hexagonal panels arranged to offer a layout maximizing interior living space. This futuristic design does not compromise the comforts of home, offering a two-storey layout complete with a living room, kitchen, bathroom and two bedrooms. Another modern twist on the traditional is that these homes are built using eco-friendly materials and methods. The design is vented on the exterior, and insulated with wood and flax. A green roof tops off these homes, complemented by solar roof panels, a wind turbine and other methods to harvest alternative forms of energy.

Waste Minimisation & Recycling

Two companies handle all waste disposals in the Faroe Islands: Kommunala Brennistøðin (KB) in the capital area and IRF (Interkommunali Renovatiónsfelagsskapurin L/F) in the rest of the Faroe Islands. Waste is divided in several categories and both companies recycle paper, iron and other metals. IRF recycles PE Big Bags and PE and PP fishing nets, tyres, electronics and glass. KB recycles tyres, electronics and refrigeration equipment. The cost depends on the waste company and waste category. Both companies incinerate waste from households and industry. The plants incinerate waste that is not recycled, deposited or termed hazardous. The latter covers batteries, chemicals, paint and anything containing heavy metals and clinical waste. Waste oil is collected from industry, harbours and vessels on a requested basis. All waste oil is recycled for heating purposes and is accepted free of charge on the condition that the collecting truck has easy access to the waste oil. Both companies dispose waste that does not fit into the other categories e.g. asbestos, insulants and other inert materials.

Extensive Agriculture & Organic Food Production

The National Farmers Co-operative (MBM) is divided into two separate units, a production division and a sales division. There is also a marketing department and an administration department. The milk producers are joint owners of the co-operative and each owns a part of the association equal to their respective milk quota.

A central dairy was established for all the Faroe Islands in order to supply all 45,000 inhabitants with fresh milk and to ensure dairy produce sales on the Faroese market. In addition, the co-operative safeguards the interests of the dairy producers, gives advice on the handling of milk, so that the dairy is able at all times to offer customers milk of the highest quality. In the view of the MBM, this goal has been achieved through the company's constant emphasis on providing both producers and customers with good service.

A central dairy was established for all the Faroe Islands in order to supply all 45,000 inhabitants with fresh milk and to ensure dairy produce sales on the Faroese market. In addition, the co-operative safeguards the interests of the dairy producers, gives advice on the handling of milk, so that the dairy is able at all times to offer customers milk of the highest quality. In the view of the MBM, this goal has been achieved through the company's constant emphasis on providing both producers and customers with good service.

Besides milk for direct consumption, the dairy produces a natural range of cream and soured products and conducts studies, both to improve quality and to develop new products, e.g. cream cheese and fruit drinks. The rapid increase in production and range of products has made it necessary to keep pace in the adaptation of the production plant. MBM has now attained an optimal utilization of its premises and machinery, and expansion is currently being planned.

MBM does not limit its activities to the production of dairy products. In 1987 it took over a company that dealt in concentrated feed and artificial fertilizers. MBM-Fodder is now performing well as a purchase and sales department, supplying farmers with cheap feed and high-quality fertilizers.

Another department of MBM supplies farmers with various types of agricultural machinery and implements and runs a repair shop for lorries, tractors and farming machinery. A substantial part of the department's activity consists of providing dairy producers with guidance and servicing their refrigeration and processing equipment, and it runs specially equipped service vehicles for this purpose.

Agricultural organizations ![]() &

& ![]() in the Faroe Islands have decided to work closely together, and have set out to modernize and streamline their structure. A common administration is to be set up to attend to overall control and so ensure that the shared resources and facilities can be utilized as effectively as possible.

in the Faroe Islands have decided to work closely together, and have set out to modernize and streamline their structure. A common administration is to be set up to attend to overall control and so ensure that the shared resources and facilities can be utilized as effectively as possible.

The new organization is located at the Forsøgsstationen research station in Kollafjørd, which is to become the centre of Faroese agriculture. In addition to the agricultural station, the station also houses the state veterinary service. MBM is a project that has proved that agriculture can be made profitable through co-operation and co-ordination. Before the establishment of MBM, the Faroes were not self-sufficient in milk, but in only a few years, production was raised and the entire market was taken over.

The Faroes are not self-sufficient in meat and other agricultural products. They produce some of their own requirements in mutton and beef. There are approximately 70,000 sheep on the islands. They graze freely all year long, and are only given a little additional fodder during the worst winters. Thus, the aim is to develop agriculture to the point where the Faroe Islands will be self-sufficient in as many areas as possible. The latest goal is to establish an abattoir for beef and mutton production. This project will be achieved on the basis of the MBM model.

The Faroes are not self-sufficient in meat and other agricultural products. They produce some of their own requirements in mutton and beef. There are approximately 70,000 sheep on the islands. They graze freely all year long, and are only given a little additional fodder during the worst winters. Thus, the aim is to develop agriculture to the point where the Faroe Islands will be self-sufficient in as many areas as possible. The latest goal is to establish an abattoir for beef and mutton production. This project will be achieved on the basis of the MBM model.

With the North Atlantic on all sides, it is not surprising that the Faroe Islands base their economy on the sea and the sustainable use of its resources. Fishery is and has been for many decades the main industry in the Faroes. Fishery products, including farmed salmon, represent more than 95% of total Faroese exports and nearly a half of the Faroese GDP.

Within the Faroese 200-mile exclusive fisheries zone, the modern Faroese commercial fishing fleet, comprised mainly of coastal vessels and long-liners as well as a number of ocean-going trawlers, exploits this diversity of marine species and stocks. Faroese access to fisheries in other zones and international waters, secured through reciprocal fisheries agreements with other countries in the region, as well as participation in regional management bodies, also provides the Faroese industry with an important supply of resources.

According to Faroese law, fish stocks in Faroese waters are the property of the Faroese people and shall be managed for the public good. The Faroese fisheries management system of fishing days, adopted in 1996, regulates demersal fisheries in the Faroese 200 mile fisheries zone. Vessels are grouped according to size and gear type, and each group is allocated a set number of fishing days per year, which are divided among the vessels. This is combined with gear regulations designed to protect juvenile fish, as well as closures of extensive areas to active gear such as trawls in order to protect nursery and spawning stocks.

According to Faroese law, fish stocks in Faroese waters are the property of the Faroese people and shall be managed for the public good. The Faroese fisheries management system of fishing days, adopted in 1996, regulates demersal fisheries in the Faroese 200 mile fisheries zone. Vessels are grouped according to size and gear type, and each group is allocated a set number of fishing days per year, which are divided among the vessels. This is combined with gear regulations designed to protect juvenile fish, as well as closures of extensive areas to active gear such as trawls in order to protect nursery and spawning stocks.

The fishing day system manages fishing capacity and effort rather than allocating specific quotas for species and stocks. This allows for mixed fisheries, giving the entire catch an economic value. As such, it has so far proven to be a flexible and responsive management tool, also providing the industry with stability.

The system has also significantly reduced the occurrence of discards of non-targeted fish, often a crucial problem in species-specific fisheries management, as well as reducing incentives for misreported catches, which confound so many fish stock assessments. Vessels can adapt their activities within a broad framework of management strategies, which sets the overall removals from any given stock at a maximum level.

Developed in close dialogue between the Ministry and fisheries organizations like the Faroe Marine Research Institute, the system has the full support of the industry. The basis for allocating fishing days according to the level of effort and the proportion of different stocks fished is reviewed through a process of consultation in which the fishing industry actively participates.

The phasing out of government subsidies to the fisheries sector in the Faroes has also been a major factor in reducing over-capacity and stimulating more effective, market-driven approaches to fisheries.

Transport

Vagar Airport, the airport in the Faroe Islands, is located on the island of Vágoy. Regular bus connections are linked to scheduled arrival and departure flights. The trip to Torshavn takes 40 minutes by car/bus. There are 12 helipads in the Faroe Islands.

The Smyril Line is one of four shipping companies operating in the Faroes who between them offer weekly scheduled direct connections by sea all year round to Iceland, England, Scotland, Norway, Sweden, Holland, Germany and Denmark. Every other week there are scheduled connections to the United States and Canada via Iceland.

The Faroe Islands have a modern infrastructure with good roads and tunnels. The roads are mainly asphalted dual track carriageways. A bridge connects the two largest islands, and tunnels connect Vagar and Borðoy to this mainland. Inter island ro-ro ferries operate on all other major routes. Scheduled cargo transport is available between most villages in the Faroe Islands daily, except Saturdays and Sundays. There are also several transport companies, which will deliver cargo by arrangement.

Strandfaraskip Landsins undertakes the services of public transport in the Faroes, and publishes a general timetable encompassing all departures by sea and on land. Transport across sounds and fjords, not connected by road, is in conjunction with the scheduled Strandfaraskip Landsins general timetable. This fully integrated state-owned (and subsidised) transport system with the Strandfaraskip Landsins ferries and the blue country buses of Bygdaleiðir, with through fares and through tickets, and the buses connecting with each other and with the ferries is described by this enthusiast.

Rising requirements for environmental protection pose a serious challenge to the shipping industry today, as do historically high fuel oil prices. Greenstream developed in the Faroes is a revolutionary new, patent pending energy saving system for ships that provides a significant reduction in fuel costs by adjusting the ship’s trim and speed so as to minimize propulsion resistance. The Faroe Islands Wind Energy Association has also looked into the possibility of demonstrating the feasibility of operating one or two hydrogen powered fishing boats.

A new ferry has been planned for Nolsoy and is considerably larger than the current ship, Ritan, and will be designed to carry 14 cars and 200 passengers. It will be a modern ship with a diesel electric propulsion system. Azimuth thrusters will be fed by two 800 kW diesel powered electrical generators. It will be possible to replace one of these generators with a hydrogen-powered generator or install a HPG in addition to the two DPGs. The designer has prepared the ship so it can easily change to HPG. Excess power from the wind farm could be converted to hydrogen fuel for this ferry.

Sustainable Tourism & Niche Marketing

In December 2007 the Faroe Islands were ranked first by a panel of 522 tourism experts in a comprehensive survey of 111 island communities throughout the world conducted by the National Geographic Centre for Sustainable Destinations and Traveler magazine. This accolade has been capitalised upon by their Tourist Board and Guide as well as travel agents like GreenGate Incoming who all seem keen to maintain the islands image for environmental and ecological quality, social and cultural integrity as well as further improve their future outlook.

A strategic decision has been taken by the 360 inhabitants on the outer islands (Utoyggjar) to move away from fossil fuels and utilise renewable energy. This is part of an effort to develop green and cultural tourism as a new source of income. Fugloy has plans to build a new Centre for Culture and Tourism powered with renewable energy. Svinoy is working in cooperation with North Adventure on a tourism project that combines a boat trip with opportunity to cut peat. Kalsoy has plans for an ecomuseum and holiday village for mountain climbing, traditional crafts and story telling. Mykines has a couple building a guest and art house in the style of an old Viking building powered by renewable energy. On Koltur there is only one family with an organic farm who have been testing a renewable energy system. Skuvoy also want to resolve the problem of relying on oil delivered in barrels to heat their homes and move to renewable sources. Stora Dimun no longer rely on diesel and have a renewable energy system comprising a wind generator with battery storage, solar panels and a heat pump. The island also has a tannery that sells hides to tourists and a new production house that makes and retails food and other commodities from local produce.

Nolsoy is situated approximately 5kms east of Torshavn and the ferry crossing takes 20 minutes. An historic house in the heart of the harbour has been renovated to become the tourist information office with a café. From here guided excursions can be arranged including one to the lighthouse at the southern-most tip of the island. The light-house has been constructed of beautiful hewn stone, has one of the world’s largest lenses and is almost three metres high; weighs four tons and is featured on the twenty kroner coin. Other tours go to places nearer the village, such as the one to Korndalur, where the princess spring and ruins can be seen. Legend has it that it was here the princess lived with her lover after being forced to flee due to the disapproval of her father, the Scottish king.

Nolsoy is situated approximately 5kms east of Torshavn and the ferry crossing takes 20 minutes. An historic house in the heart of the harbour has been renovated to become the tourist information office with a café. From here guided excursions can be arranged including one to the lighthouse at the southern-most tip of the island. The light-house has been constructed of beautiful hewn stone, has one of the world’s largest lenses and is almost three metres high; weighs four tons and is featured on the twenty kroner coin. Other tours go to places nearer the village, such as the one to Korndalur, where the princess spring and ruins can be seen. Legend has it that it was here the princess lived with her lover after being forced to flee due to the disapproval of her father, the Scottish king.

The world’s largest colony of storm petrels is found on Nolsoy and island ornithologist, Jens Kjeld Jensen arranges nightly walks where this beautiful small bird can be watched and, not least, listened to. Another name always mentioned in connection with Nólsoy is Ove Joensen, a local who rowed single-handed 900 sea miles from the Faroe Islands to Langelinie in Copenhagen. His boat, the Diana Victoria, is on display in the basement of the tourist information centre. Another historic house, dating from the 1600’s has been converted into a museum.

To help further the sustainable development of wildlife tourism three Faroese organisations are partners in the Wild North project including Sjoferdir, a family owned company that offers boat tours to the Vestmanna bird cliffs and grottos which are one of the biggest tourist attractions in the Faroe Islands. Vestmanna and Koltur are both referred to by Ilan Kelman in his project investigating how small islands and their communities could achieve sustainability through managing vulnerabilities to their heritage.

Besides the wealth of wildlife, the Faroe Islands are by no means culturally poor or deprived. In fact, the vocal traditions have been exceptionally rich and versatile; one reason being that the written Faroese language was not established until 1854, and not accepted in public by the Danish authorities until 1938. All stories, myths, songs and ballads were handed down from one generation to the next orally, and people had to learn by heart to take part in this exchange, which today sums up most of their cultural heritage. Again, remoteness played a decisive part in the development; as there were no musical instruments of significance until the mid 1800s the voice was the only music-making tool available, and as a result singing is deeply anchored in their national identity. One of the most unique cultural features is the chain dance, which originally was a mediaeval ring dance. The rhythm is quite quirky and the ballads about kings and heroes may have several hundred verses. Today, there is rich music scene for visitors to enjoy including the summer G! festival, one of the most popular in Europe, and also a dynamic art museum.

Besides the wealth of wildlife, the Faroe Islands are by no means culturally poor or deprived. In fact, the vocal traditions have been exceptionally rich and versatile; one reason being that the written Faroese language was not established until 1854, and not accepted in public by the Danish authorities until 1938. All stories, myths, songs and ballads were handed down from one generation to the next orally, and people had to learn by heart to take part in this exchange, which today sums up most of their cultural heritage. Again, remoteness played a decisive part in the development; as there were no musical instruments of significance until the mid 1800s the voice was the only music-making tool available, and as a result singing is deeply anchored in their national identity. One of the most unique cultural features is the chain dance, which originally was a mediaeval ring dance. The rhythm is quite quirky and the ballads about kings and heroes may have several hundred verses. Today, there is rich music scene for visitors to enjoy including the summer G! festival, one of the most popular in Europe, and also a dynamic art museum.

Biodiversity & Protected Areas

The Faroe Islands are located on the southern boundary of the European Arctic and environmental data on the ecosystem, marine as well as terrestrial, are therefore of great interest to both the scientific community and to organizations involved in environmental monitoring and assessment. In order to provide a more direct and user-friendly access to the environmental data gathered in the region, the Faroese Museum of Natural History, the Environment Agency and Faroe Marine Research Institute have established ENVOFAR. The marine benthic fauna of the Faroe Islands is covered by the Biofar project and natural history recording more generally by Faroe Nature.

There are no protected areas as such in the Faroe Islands although BirdLife International (and local affiliate the Faroese Ornithological Society) list 19 Important Bird Areas. It is estimated that there are some 2 million pairs of seabirds in different colonies spread around islands. The largest change in recent times was the huge invasion of fulmars in the early 19th century. Fluctuations in the seabird populations stem from a variety of natural causes, and in general the populations have seen a decrease since the late 1950s. In the 1980s and early 1990s there was a scarcity of food in the seas around the Faroe Islands. This scarcity was an issue for everyone on the islands as fishing is a major industry, and it also led to a reduction in seabird numbers. The Faroes Oil Industry Group produced a number of valuable environmental reports in 2000/01 on the populations, distribution, dispersion and vulnerability of marine birds, marine mammals and cetaceans.

There are no protected areas as such in the Faroe Islands although BirdLife International (and local affiliate the Faroese Ornithological Society) list 19 Important Bird Areas. It is estimated that there are some 2 million pairs of seabirds in different colonies spread around islands. The largest change in recent times was the huge invasion of fulmars in the early 19th century. Fluctuations in the seabird populations stem from a variety of natural causes, and in general the populations have seen a decrease since the late 1950s. In the 1980s and early 1990s there was a scarcity of food in the seas around the Faroe Islands. This scarcity was an issue for everyone on the islands as fishing is a major industry, and it also led to a reduction in seabird numbers. The Faroes Oil Industry Group produced a number of valuable environmental reports in 2000/01 on the populations, distribution, dispersion and vulnerability of marine birds, marine mammals and cetaceans.

In October 2007 a group of seabird experts meeting in the Faroes made a press release. Their conclusion was that “large scale, climate related ecological changes have disrupted the food web of marine birds in Nordic waters. Over recent years, a decreasing number of birds have shown up in the colonies, and local populations are in trouble with few chicks being raised. Comprehensive and complex changes are now happening in the marine ecosystem, underlining more than ever the need to manage all other factors, which affect seabirds such as commercial fisheries, oil spills, seabird harvest and environmental pollutants.”

It was reported that Arctic tern chicks on Nolsoy and kittiwake chicks on Mykines started to die from starvation on 20 July 2009. These seabirds seemed to have a successful breeding season in 2009, with plenty of sand eels late in June and during the first 14 days of July. Each time they returned from fishing, adult terns were bringing 2-4 sand eels to their chicks. However, there was a sudden change on 23 July, when parents spent more time at sea and only brought back a single sand eel to their chicks each time. As a result, 500 chicks died over two nights in the Nolsoy colony leaving only approximately 100 left alive. This was the fifth consecutive disastrous breeding season for Arctic terns and it was the same situation for the puffin colonies as well. Fortunately, in June 2008 the three separate landowners of Nolsoy had agreed to protect the puffin for the next two years by not allowing any traditional catching at their main colony.

The natural vegetation of the Faroe Islands consists of over 400 different plant species and is dominated by Arctic-alpine plants, wildflowers, grasses, moss and lichen. Wasps were accidentally introduced in 1999 when grass for a football pitch was imported and there are 91 species of spider. Only three species of wild land mammals – mountain hare, brown rat and house mouse - are found in the Faroes today, all introduced by humans. Jens Kjeld Jensen has extensive information about the flora and fauna of Nolsoy on his website.

Grey seals are very common around the shorelines and many different species of cetacean occur in the waters around the Faroe Islands. Of these, the small and abundant pilot whales are taken in the Faroe Islands for their meat and blubber in a whale drive, which is organised on the community level and regulated by national legislation. This traditional form of whaling was once common all across the North Atlantic, but is now unique to the Faroe Islands. This is due to the fact that both the meat and blubber of pilot whales have long been and continue to be a staple part of the national diet. Nevertheless, the pilot whale drive is still highly controversial.

Grey seals are very common around the shorelines and many different species of cetacean occur in the waters around the Faroe Islands. Of these, the small and abundant pilot whales are taken in the Faroe Islands for their meat and blubber in a whale drive, which is organised on the community level and regulated by national legislation. This traditional form of whaling was once common all across the North Atlantic, but is now unique to the Faroe Islands. This is due to the fact that both the meat and blubber of pilot whales have long been and continue to be a staple part of the national diet. Nevertheless, the pilot whale drive is still highly controversial.

The Faroe Islands cooperate internationally through appropriate international organisations on the conservation of whales and the management of whaling. Whaling in the Faroes has over the years adapted to modern standards of animal welfare. The annual average catch of c. 900 pilot whales, from a stock estimated by scientists to number over 700,000 in the North Atlantic, is fully sustainable.

Whales are shared among the participants in a whale drive and residents of the local district where they are landed. The economic value of pilot whales is measured against the economic and environmental costs of importing the same amount of food, equivalent to some 30% of all meat produced locally in the Faroes.

Internationally adopted principles for the conservation and sustainable use of living marine resources apply to all components of the marine ecosystem, including marine mammals. Ensuring that utilisation of these resources is sustainable, whether for subsistence or commercial purposes, requires a sound scientific basis and international cooperation on the conservation and management of highly migratory stocks.

Integrated Development Planning

Economic troubles caused by a collapse of the Faroese fishing industry in the early 1990s brought high unemployment rates of 10 to 15% in the mid 1990s. Unemployment decreased in the later 1990s, down to about 6% at the end of 1998. By June 2008 unemployment had declined to 1.1%, before rising to 3.4% in early 2009. Nevertheless, the almost total dependence on fishing and fish farming means that the economy remains extremely vulnerable. Petroleum found close to the Faroese area gives hope for deposits in the immediate area, which may provide a basis for sustained economic prosperity.

Since 2000, new information technology and business projects have been fostered in the Faroe Islands to attract new investment. The introduction of Burger King in Torshavn was widely publicized and a sign of the globalization of Faroese culture. It is not yet known whether these projects will succeed in broadening the islands' economic base. The islands have one of the lowest unemployment rates in Europe, but this should not necessarily be taken as a sign of a recovering economy, as many young students move to Denmark and other countries once they have left high school. This leaves a largely middle-aged and elderly population that may lack the skills and knowledge to fill newly developed positions on the Faroes.

The Faroese population is spread across most of the area; it was not until recent decades that significant urbanisation occurred. Industrialisation has been remarkably decentralised, and the islands have therefore maintained quite a viable rural culture. Nevertheless, villages with poor harbour facilities have been the losers in the development from agriculture to fishing, and in the most peripheral agricultural areas, also known as the outer islands (Utoyggjar), there are scarcely any young people left. In recent decades, the village-based social structure has nevertheless been placed under pressure, giving way to a rise in interconnected "centres" that are better able to provide goods and services than the badly connected periphery. This means that shops and services are now relocating en masse from the villages into the centres, and slowly but steadily the Faroese population is concentrating in and around the centres.

In the 1990s the old national policy of developing the villages (Bygdamenning) was abandoned, and instead the government started a process of regional development (Økismennin). The term "region" referred to the large islands of the Faroes. Nevertheless the government was unable to press through the structural reform of merging the small rural municipalities in order to create sustainable, decentralised entities that could drive forward regional development. As regional development has been difficult on the administrative level, the government has instead made heavy investment in infrastructure, interconnecting the regions. In general, it is growingly less valid to regard the Faroes as a society based on separate islands and regions. The huge investments in roads, bridges and sub-sea tunnels have bound the islands together, creating a coherent economic and cultural sphere that covers almost 90% of the population.

However, it is vitally important that the government does not disregard the eight outer islands and indeed must provide extra support to their representative Association. The Research Center for Social Development formally attached to the University of the Faroes since 1 January 2008 works closely with this Association through its research projects. In particular, this Center is a partner in the Economusee Northern Europe project which is designed to combine culture, craft and tourism to create an economy platform for craft artisans practicing traditional techniques in order to help the craft survive and create new jobs. This involves a blacksmith in the village of Trollanes on the island of Kalsoy. The Center is also a partner in the ‘Retail in Rural Regions’ project whose overall objective is improved service quality in small communities by supporting the survival, development and growth of rural retail shops.

An essential stimulus for these and other development projects is the availability of funding for which the Faroese are well endowed through their own Research Council, Nordic Atlantic Cooperation (NORA) and the EU Northern Periphery Programme.

Climate Change Mitigation & Adaptation Measures

In December 2009 the Faroese parliament passed a resolution supported by all political parties that commits the Faroe Islands to a reduction of greenhouse gas emissions by at least 20% by 2020. Their clear and concise climate policy document with an action plan based on the implementation of specific measures in six areas where considerable and lasting reductions can be made with immediate and long-term effect can be downloaded from a dedicated website.

Acknowledgements:

Inga Simonsen, Ministry of Foreign Affairs

Susanna Sorensen, Head, Visit Faroe Islands

Faroese Earth & Energy Directorate (Jardfeingi)